Urban Biodiversity: Building Community Capacity for Ecological Restoration

Urban Biodiversity: Building Community Capacity for Ecological RestorationNathalie Dechaine and Chris Strashok

Published February 1, 2010

Case Summary

The Capital Regional District (CRD) of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada is characterized by a mild climate, rich in diverse biotas that are in some cases, endemic solely to the region. Its temperate climate makes the region a desirable place in which to live, but also open to the introduction of alien invasive species that threaten its indigenous biological diversity.

While local governments recognize the associated costs and risks of doing nothing, they do not have the capacity, knowledge or political will to act on this problem of isolation from community resources, not the least of which is human capital. The extent of the problems of alien invasive plant species cannot be addressed by the few formal small ecological restoration projects currently being conducted within the CRD. In response, volunteer groups have approached local governments or have initiated invasive species removal from public lands independently.

Two case study restoration projects were examined: Mount Douglas Park and Mill Hill Regional Park. This study explores several tools and processes that mobilize social capital to engage in ecological restoration to sustain local indigenous biological diversity. In particular, the role of bridging social capital to increase access by volunteer groups to augment access to resources by local government is examined, on the assumption that the creation of novel collaborative partnerships is a critical way to sustain native plant diversity in the region, and elsewhere in Canadian communities.

Sustainable Development Characteristics

Natural areas in the urban environment are important for several reasons. Ecologically, they sustain all living beings, as well as human social and economic systems. Natural areas contribute to conserving vital ecosystem services on which we all rely. For example, they provide services such as food, water, timber and fibre; the regulation of climate, floods, disease, wastes, and water quality; cultural services such as recreation, aesthetic enjoyment, and spiritual fulfillment, and; supporting services such as soil formation, primary production, photosynthesis, and nutrient cycling (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005; Daily, 2000). Natural areas also provide close neighbourhood access to nature for people living in the city while increasing social integration and interaction among neighbours through restoration projects (Chiesura, 2004).

Critical Success Factors

The continued success of ecological restoration projects in the CRD of Victoria and application to other natural areas is dependent upon several key steps being in place—enhanced collaborative approaches, education, increased access to resources (including indigenous plants), maximizing volunteer capital, and changing policy and legislation.

Community Contact Information

Nathalie Dechaine, M.A., B.A.

Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

Email: nathaliedechaine@hotmail.com

What Worked?

The Mount Douglas Park and Mill Hill Regional Park restoration projects had varying levels of formal government involvement, financial and volunteer support, therefore, what worked for each case study was very different.

When a governmental agency leads a project such as the Mill Hill Regional Park restoration, it stands a much greater chance of continuing over time given government stability. In government-run projects, core funding is provided to pay for deliberate planning and coordination for the project such as expertise and volunteer recruitment and training support. Government-run projects are more traditionally scientific and deliberate in their approaches. The coordinator of the Mill Hill Regional Park project recognized that ecological restoration in and of itself impacts the ecosystem and that some risk to the surrounding environment must be managed to facilitate the project’s outcomes. Because of this, the Mill Hill Regional Park restoration project reserved certain tasks in sensitive environments for paid staff, but the possibility still existed that paid workers trampled nearby native vegetation, causing collateral damage and soil disturbance, as much as a well-trained volunteer might.

In the community-based projects, like Mount Douglas Park, community involvement is the driver for these projects and, therefore, volunteers work more independently. With direction from the District of Saanich staff, guidance and access to resources, the community was resourceful and effective at engaging social capital to conserve urban biological diversity. This flexibility and mobilization of community social capital allowed this group to work on multiple projects at one time while reaching out to schools, members of the public and university programs designed to educate local residents about ecosystems, their value and their vulnerability.

What Didn’t Work?

The unofficial work by caring community members poses challenges for restoratoin projects in terms of both public safety and environmental concerns. When citizens lack the requisite knowledge necessary to be effective and safe in their efforts, and take matters into their own hands, negative public perception of ecological restoration can be potentially fostered as plant debris is left on-site, looking unsightly and invasive species can be spread further when not disposed of properly.

Financial Costs and Funding Sources

The funding for these two restoration cases are different. Mill Hill Regional Park receives substantially more funding and focuses on only one project, while Mount Douglas Park has several different projects, one of which is overseen by District of Saanich staff, but most are overseen by volunteer coordinators.

Since the restoration project in Mill Hill Regional Park is funded by the federal government through the Government of Canada’s Habitat Stewardship Program, reporting requirements are such that CRD Parks formally records and documents aspects of the project to meet the federal funding requirements. This is an effective incentive to keeping the information well-organized and conducting monitoring.

In Mount Douglas Park, while the Garry Oak Restoration Project (GORP) has formal administratrive oversite of the project by District of Saanich staff, and includes a restoration plan, site inventories and monitoring, very little information is formally documented, however, in the volunteer-led restoration projects either by the community groups or by the District of Saanich. Consequently, it was difficult to directly compare costs with those associated with the Mill Hill Restoration Project.

Research Analysis

Two case studies involving ecological restoration projects in the CRD of Victoria were selected--the Mount Douglas Park restoration explores projects initiated by a government agency, while the Mill Hill Regional Park restoration explores a community-based approach. There are several restoration projects underway in the former including riparian, Douglas-fir forest and Garry oak ecosystems. The latter has only one project that is focused on the Garry oak ecosystem. Both case studies differ in their access to resources, and are compared and contrasted for similarities and differences. By comparing and contrasting these case studies, the intent was to assess under what conditions community volunteers can assist in restoring native ecosystems by removing introduced invasive plant species, and how government agencies can work with this potential to realize their own goals and objectives. Thirteen people were interviewed and data was analyzed for opportunities and barriers to bridging community social capital and governmental agencies.

Detailed Background Case Description

The CRD of Victoria, British Columbia is characterized by a mild climate, and rich in diverse biotas that are in some cases, endemic solely to the region. The region's temperate climate also makes it a desirable place in which to live, but also a climate in which alien invasive species can prosper. Invasive plants are considerred one of the major threats to the biological diversity in this area.

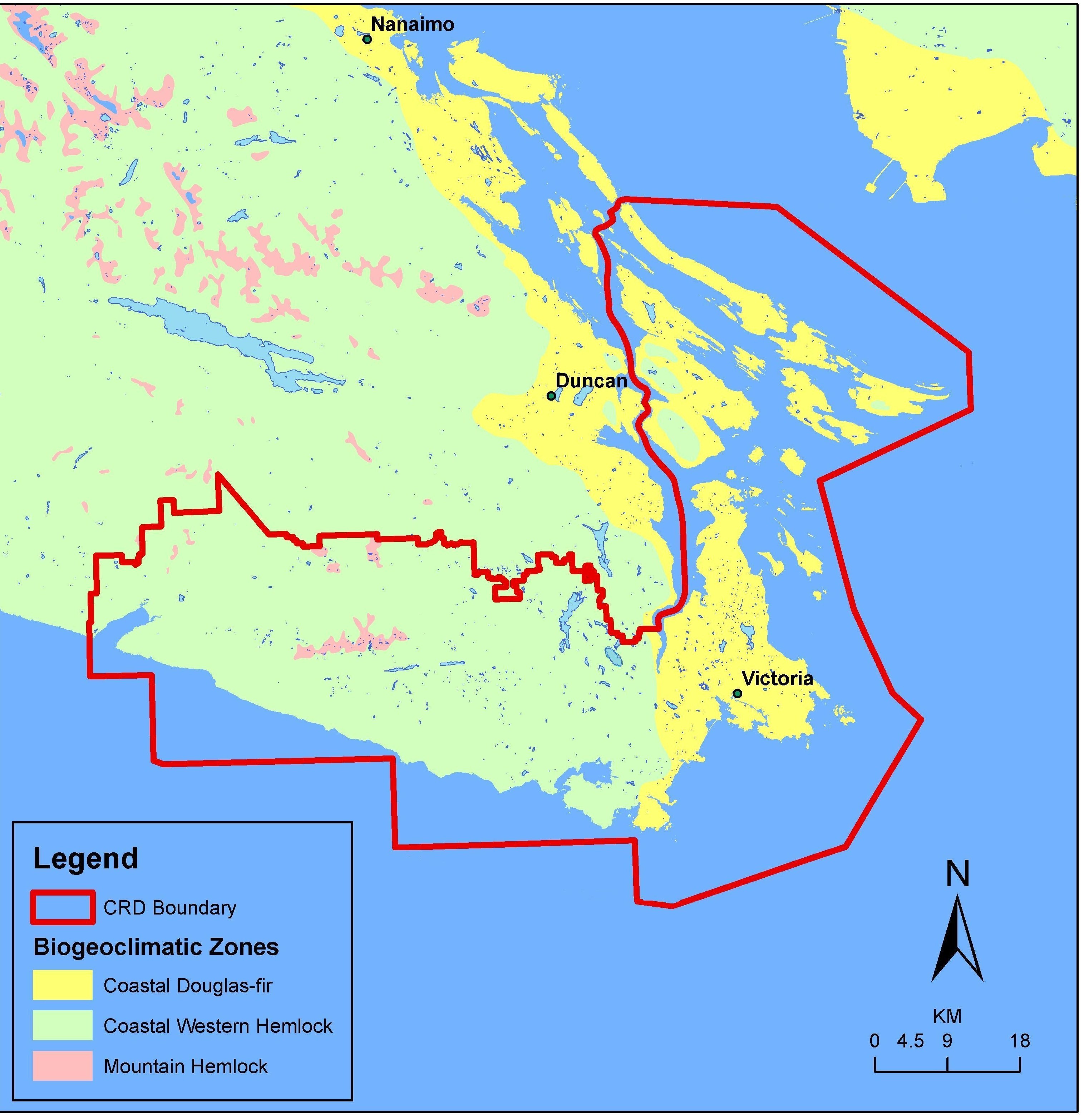

The CRD is located in both Coastal Western Hemlock (CWH) and Coastal Douglas-fir (CDF) biogeoclimatic zones. This case study focuses on the portion of the CRD that falls within the CDF zone which consists of a small strip along south-eastern Vancouver Island, extending to the Gulf Islands. Although it is one of the smallest biogeoclimatic zones, it has the highest number of species at risk per unit area of any zone in B.C. (Holt 2001 as quoted in British Columbia Ministry of Environment, 2006).

(Source: Data Warehouse, Province of British Columbia 2009)

As its name implies, the predominant forest type in the CDF zone is Coastal Douglas-fir. Garry oak ecosystems, however, which are endemic to Canada and one of the country’s most endangered ecosystems, are also found here. This zone is best typified by its Mediterranean climate, which is caused by the rain-shadow effect of the Olympic and Vancouver Island Mountains. This climate is unique to only 1% of Canada (Schaefer, 1994). Mild, wet winters and dry summers, with a mean annual temperature that ranges from 9.2 to 10.5 degrees Celsius allow unique plant assemblages to grow in this part of Canada. The Coastal Douglas-fir biogeoclimatic zone currently contains 261 plant and animal species and 36 ecosystems that are provincially listed as at-risk (British Columbia Ministry of Environment, 2009).

Within this zone, the CRD is largely developed and makes up 13 incorporated Municipalities and three large unincorporated electoral areas: Saltspring Island, Southern Gulf Islands and Juan de Fuca, and extends from the Gulf Islands to Port Renfrew. The CRD also has a relatively large parks system set aside to protect natural values including biodiversity. The total amount of natural areas in protected area status in the CRD now approximates 24,000 ha or over 10% of the land base (Capital Regional District, 2009). These parks and other protected areas vary considerably in their roles and capacities to protect natural area values. Some parks provide intensive recreational opportunities that keep people and their community healthy and active. While others are larger, less developed and protected areas that have a greater role in conserving the biological diversity represented in this region.

The two restoration projects studied are in Mount Douglas Park and Mill Hill Regional Park, two ecologically similar parks. Mount Douglas Park is located in and managed by the District of Saanich. There are several restoration projects underway in Mount Douglas Park in various habitats; riparian, Douglas-fir forest and Garry oak ecosystems. The Garry Oak Restoration (GORP) in Mount Douglas Park is the one project overseen by the District of Saanich staff while the remaining projects in the park are coordinated by volunteers associated with the Friends of Mount Douglas Park Society and varying restoration objectives.

CRD Parks manages Mill Hill Regional Park. It is located mostly in Langford with a small section occurring in View Royal. There is only one restoration project in Mill Hill Regional Park that is focused on the Garry oak ecosystem and only on relatively few invasive species such as Scotch broom and Daphne laureola. This project is overseen by CRD Parks’ Environmental Conservation Specialist. The Mill Hill Regional Park project is funded in partnership with CRD Parks and the federal government through the Government of Canada’s Habitat Stewardship Program.

Invasive species are second only to land alienation in the threats they pose to natural ecosystems and biodiversity (Land Trust Alliance of B.C., 2009; Murray and Pinkham as quoted in Polster 2004). The impacts of invasive plants on ecosystems are complex. Invasive plant species compete with native plants for resources and become dominant over other native species (Coastal Invasive Plant Committee, n.d.), change soil nutrient regimes, and can modify the successional trajectory of ecosystems (Polster, 2004). Since plants exist near the bottom of the food web, changes to their composition structure and function can affect subsequent levels in the food web. While the physical competition of invasive plants with native plants may be obvious, the full extent of indirect impacts may be yet unrealized (British Columbia Ministry of Forests and Range, n.d.).

Human activities within the portion of the CRD of Victoria located in the Coastal Douglas-fir (CDF) biogeoclimatic zone have modified 80% of this area to such an extent that the natural ecosystems are no longer present (British Columbia Ministry of Environment, 2006). Further to this, Austin et al. (2008) identifies six major stresses that continue to threaten the species and ecosystems in the region:

- species disturbance ( ecosystem conversion, human-caused disturbance of natural ecosystems for human use);

- ecosystem degradation (structural changes to natural systems from activities such as forest harvesting or water diversion);

- alien species (human dispersal of species outside of their native range);

- environmental contamination (toxins released into natural systems);

- species changing their behaviour due to human activities; and,

- species mortality (directly killing individual organisms).

In the United States, the assessed annual damage costs from introduced plants and animals for the year 2000 was set at $137 billion, and is considered an underestimate (Perrings et al., 2002). In the CRD of Victoria, private and public land managers currently incur the costs of dealing with these introduced plants without a central reporting agency so the economic impact of invasive plants are largely unknown for this region. The economic costs of introduced species are largely externalized to the environment, public agencies as well as private citizens and businesses.

Economically, natural areas add value to a locale through increased aesthetic and property values. A study of properties in the Lower Mainland and south Vancouver Island found that residential property values increase by 15-20% when adjacent to green areas and that people who live near greenways tend to live in their houses longer than those who do not (Quayle and Hamilton 1999, as quoted in Habitat Acquisition Trust, 2004). Thus, natural areas increase the economic and the social wealth of communities because less homeowner turnover rates results in more stable neighbourhoods.

Socially, ecological restoration provides a positive opportunity to engage the public in experiential knowledge about native ecosystems and biodiversity at the landscape level, as well as providing a sense of hope to counter some of the negative impacts humans have on the natural environment. This coming together over a specific cause helps to build further social capital. While the ultimate goal of rehabilitating natural areas is indeed ecological, the social benefits and motivations of people living in the area will ultimately enhance the success of environmental restoration initiatives. If environmental goals are considered without managing the social framework in which the issues arise, it is unlikely these objectives will be sustainable in the long term. By understanding and connecting to the ecology and by directly participating in these efforts, these connections extend to individual private properties and with one another, fostering greater respect and cooperation in both the ecological and social contexts.

Conclusions

Participants in the study recognized that it was not just the invasive species growing in protected areas that posed a problem, but also poorly regulated importation and cultivation of invasive species as horticultural plants, and a lack of public awareness and/or due care with regard to the impact of invasive species growing on public lands, and especially private lands. They also reported that the spread of invasive species is exacerbated by development for two main reasons: as more people move into an area they plant, transport and dispose of garden ornamentals close to natural areas; and, as more people recreate in natural areas, they or their animals serve as vectors to accidentally spread alien invasive plants within and between natural areas.

All of the participants recognized the ecological values of restoration with the main goal of increased biodiversity, restored ecological capital and its link to enhanced community resilience (Dale, submitted). Some interviewees believed that ecological restoration was an inherently value-based activity that held an ethical responsibility for nurturing the ecosystems in which they lived. More than half of the participants also extended the goals and values of ecological restoration to include restoring the human connection with each other and with the natural environment. These participants noted that by working together on a shared goal you build connections with each other, bringing community together, and reintegrating community with an awareness of the impacts on their place and actions. By building these community networks, many interviewees observed that this also helped to gain the support of the surrounding community. By increasing awareness and education in the community around the importance of urban biodiversity, greater local agency (Newman and Dale, 2005) is engendered, changing the current trend of ambivalence and apathy. In turn, this further empowers the volunteers and gives meaning to the idiom ‘think globally, act locally’.

There are risks, however, associated with performing ecological restoration activities that need to be considered and accounted for, such as collateral damage, public misperception, uncoordinated priorities and scale of restoration, as well as lack of knowledge and changing human attitudes. For example, some challenges that arose for the District of Saanich during their project were the following.

Small, medium and large English holly (Ilex aquifolium) trees are being cut down in Mount Douglas Park. This practice does not, however, produce the desired results as the holly re-sprouts from the base and some of the debris left behind contains many ripe berries which the birds eat and disperse around the Park and other surrounding areas. Also, as the cut portions of the holly trees dry out, in some cases the trees are left upright or leaning and they potentially serve as ladder fuel. Ladder fuel is forest litter that can serve to elevate ground fire to the upper canopy in the event of a fire.

In another case, a concerned citizen cut and piled large amounts of Scotch broom adjacent to the Little Mount Douglas GORP site. The manner in which the broom was cut left large sharp stems on which park visitors could easily be injured. The broom pile smothered the plants, mosses and lichens under it while there is evidence that chemicals that leach out from dead broom can alter the soil in the immediate area, exacerbating erosion and stifling natural recovery.

Also, in certain situations invasive plants may be the only thing preventing erosion, and in some cases, animals have adapted to using the invasive species as habitat. By removing invasive species there may be unintended harm to the ecology in the existing area. Interventions in dynamic and complex systems that we do not fully understand (Weddell, 2002, Dale, 2001) often have unintended consequences, even ones designed for restoration. Even though the efforts of the individuals may be well intentioned, the approaches tend to favour one species or one ecosystem over another without consideration of the overall system dynamics. These ecosystems also operate on time scales that are hundreds and thousands of years old. How can you judge if what has been done is of help or destructive? There needs to be a long-term vision and plan when conducting ecological restoration.

In order to sustain biodiversity in the urban environment, engaged citizens and the private sector need to work collaboratively together in novel partnership arrangements, formal and informal, with all levels of government and public institutions. There are several tools that are available to build the capacity needed to conserve biodiversity in the CRD: collaboration, education, increased access to resources, and changes to policy and legislation.

Integrated and collaborative approaches are a means to increase capacity, leverage existing resources, share information and increase bridging social capital. It also helps to address the issues associated when small groups are working in isolation. Local governments could actively stimulate research partnerships by engaging the research community and graduate students to examine and compile best management practices bridging knowledge gaps and increase access to intellectual wealth by disseminating this information through a central repository that can be accessed by communities.

Education and awareness campaigns help to highlight the need for all of society to participate in reducing the financial, ecological and social costs of invasive species. Education campaigns were key components to the success of both the Mount Douglas Park and Mill Hill Regional Park restoration projects helping to change public attitudes to participating in ecological restoration. Participation increased awareness about local ecology, invasive species and reinforced the roles that each approach contributes to building knowledge and ameliorating biodiversity.

Increased access to resources—financial, ecological and human capital is a critical success factor. Lack of money was seen to be one of the largest obstacles for conducting and sustaining ecological restoration projects. Both case study restoration projects had support from various levels of government in the form of funding and access to physical resources, which helped to make these projects successful. Other forms of funding also need to be examined such as: tax levies on development, establishing not-for-profit organizations for ecological restoration, working in partnership with businesses and the emerging carbon market. Diversifying the sources of funding for restoration projects will help make them more successful and sustainable.

Making use of volunteers was a strategy employed by the projects to overcome the lack of funding for paid staff. Volunteers still require, however, investment in training, coordination and support, so there must be at least one designated position to manage the volunteers in a way that is consistent with the ecological restoration goals of the management agencies, if mutually beneficial goals are to be achieved.

Access to native plants was also cited as a major barrier. Access to indigenous plants propagated with local genetics can be facilitated by greater collaboration between the community groups, academia, non-profit societies and governmental agencies. For example, native plants could be propagated through existing programs such as the Restoration of Natural Systems at the University of Victoria or in the educational horticultural programs at Glendale Gardens, clear examples of research-community partnerships.

With respect to policy and legislation, there are very few legal tools that exist to specifically address invasive species that are not associated with preventing agricultural harm. This means that if a species is not listed under that legislation, there is very little legal authority for invasive species removal, which makes it difficult to garner support for performing ecological restoration projects, impeding efforts before they even begin.

Even when legal tools exist, changes need to be made to reflect a more dynamic framework that is responsive to addressing new alien invasive species, particularly if they are dangerous or pose serious economic and or ecological risks.

These tools, the knowledge gained from each project, and the mobilization of local social capital have the potential to help directly in ameliorating the threats posed by invasive species. The challenge will be for governments to manage community-driven demand into effective opportunities for action and integrated decision-making framework optimizing volunteer capital.

Strategic Questions

- What are the legal provisions for invasive species in other municipalities and provinces?

- Emerging carbon markets is mentioned as a possible funding source. What are some other unique funding sources that could be used to finance ecological restoration projects?

- What are some of the challenges of trying to apply a conservation paradigm to dynamic ecosystems? Is this the right thing to do?

- What role can governments and their policies play in supporting urban biodiversity in this community and other communities?

- Is social capital really necessary for dealing with urban biodiversity?

- How can communities deal with invasive species on private lands?

- What are some of the other threats to urban biodiversity and how can they be addressed?

- How can governments honour volunteer capital and ideally, contribute to enhanced local social capital?

Resources and References

Austin, M.A., Buffet, D. A., Nicolson, D.J., Scudder, G.E., & Stevens, V. (Eds.). (2008). Taking nature’s pulse: The status of biodiversity in British Columbia. Victoria: Biodiversity BC.

British Columbia Ministry of Environment. (2006). Develop with Care: Environmental guidelines for urban and rural land development in British Columbia. Section Five-Regional Information Packages, Vancouver Island Region. Retrieved June 9, 2009 from: http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/wld/documents/bmp/devwithcare2006/develop_with_care_intro.html.

British Columbia Ministry of Environment, (2009). Conservation Data Centre. BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer. Retrieved July 27, 2009, from http://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/.

British Columbia Ministry of Forests and Range (n.d.). Retrieved June 9, 2009 from: http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/hfp/biocontrol/index.htm.

Capital Regional District, (2009). State of Environmental Indicators Report Update. Retrieved June 14, 2009 from: http://www.crd.bc.ca/rte/statereports/2006/documents/RTESOEIUpdatefinaltext.pdf.

Chiesura, A. (2004) The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landscape and Urban Planning. 68, 129–138.

Coastal Invasive Plant Committee, (n.d.). Retrieved June 06, 2009 from http://www.coastalisc.com.

Daily, G.C. (2000). Management objectives for the protection of ecosystem services. Environmental Science and Policy 3(6), 333-339.

Dale, A. (2001). At the edge: sustainable development in the 21 century. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Dale, A. (submitted). Diversity: Why is the human species so bad at difference? Journal of Urban Studies.

Habitat Acquisition Trust Manual. (2004). Protecting Natural Areas in the Capital Region. Retrieved February, 13, 2009 from: http://www.hat.bc.ca/attachments/016_HATManual.pdf.

Land Trust Alliance of British Columbia (2009). Credible conservation offsets for natural areas in British Columbia. Summary Report by Brinkman, D., & Hebda, R.J., Edited by Penn, B. Retrieved June 21, 2009 from: http://www.landtrustalliance.bc.ca/docs/LTABC-report09-web2.pdf.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis. Retrieved June 13, 2009 from: http://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.354.aspx.pdf.

Newman, L. and A. Dale. 2005. The role of agency in sustainable local community development. Local Environment, 10(5): 477-486.

Perrings, C., M. Williamson, E. B. Barbier, D. Delfino, S. Dalmazzone, J. Shogren, P. Simmons, P. and Watkinson, A. 2002. Biological invasion risks and the public good: an economic perspective. Conservation Ecology. 6(1): Retrieved January 20, 2009 form: http://www.consecol.org/vol6/iss1/art1.

Schaefer, V. (1994). Urban Biodiversity. In L.E Harding & E. McCullum (Eds.). Biodiversity in British Columbia: Our changing environment. (pp. 307-318). Vancouver: UBC Press.

Weddell, B.J. (2002). Introduction: Balance and flux. In Conserving living natural resources in the context of a changing world. (pp.1-8). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Comments on Strategic Questions 3, 5 and 6

3. What are some of the challenges of trying to apply a conservation paradigm to dynamic ecosystems? Is this the right thing to do?

Part of the problem with devising a conservationist approach to a dynamic ecosystem is that the very nature of conservation is to prevent change by protecting the ecosystem from the perceived or realized effects of anthropogenic activities. The resilience of an ecosystem is based on its ability to be diverse and dynamic (Higgason & Brown, 2009). The adaptive capacity of an ecosystem is also highly dependent on the resilience of the system. Therefore, when applying a conservation paradigm to dynamic ecosystems, the resilience and adaptive capacity must also play an important role along with flexible management practices that also allow the system to naturally defend itself.

Not only is an integrated and dynamic conservation approach to ecological restoration necessary, but also measures must be taken to identify and control or mitigate the negative impacts in the first place to prevent the necessity for the restoration (Gayton, 2001).

Although the introduction of invasive species can be detrimental to an ecosystem, some can also help the system become more resilient to foreign introductions.

5. Is social capital really necessary for dealing with urban biodiversity?

Social capital is an integral component to the sustainability of urban biodiversity (UB). By collaborating with local communities, educating those who are affected becomes much more effective. This is the social component of a triple bottom line approach to sustainability. Education is the key to successful understanding and stewardship towards protecting urban biodiversity. Without social capital, the local buy-in and involvement can be limited. As mentioned above biodiversity is essential for resilience and adaptive capacity.

In the case of invasive species, and as described in the case study, social capital can provide an invaluable resource from which to draw knowledge, ideas, physical labour and even capital to maintain the well-being of urban systems.

6. How can communities deal with invasive species on private lands?

If a community is hosting an educational forum on local invasive species, all private property owners in the area should be targeted for participation. Education again is the key to informed decision making and the sustainability of a management practice. All efforts should high profile and visible throughout the communities that are intended to improve the quality of the local ecosystem.

By allowing private land owners the same access to the resources made available to public lands for invasive species eradication, participation may be increased.

References:

Higgason, K. D., & Brown, M. (2009). Local solutions to manage the effects of global climate change on a marine ecosystem: a process guide for marine resource managers. ICES Journal Of Marine Science / Journal Du Conseil, 66(7), 1640-1646.

Gayton, D.V. 2001. Ground Work: Basic Concepts of Ecological Restoration in British Columbia. Southern Interior Forest Extension and Research Partnership, Kamloops, B.C. SIFERP Series 3.

Re: Urban Biodiversity: Building Community Capacity

This case study, Urban Biodiversity: Building Community Capacity for Ecological Restoration by Chris Strashok, is particularly interesting because of its focus on engaging individuals and groups to help protect plant biodiversity. Human communities for plant communities--a nice alternative to other trends we see.

The two restoration areas of Garry Oak ecosystems, within larger Coastal Douglas Fir zones in the Victoria region, provide an effective contrast of Government led and Community led approaches. The study provides a comprehensive outline of how important these ecosystems are to overall biodiversity, listing compelling detail on their relative uniqueness and high number of endemic plant species. These areas are also cherished for their recreational uses.

The research conclusions appear to match what would generally be expected, especially regarding the need for better access to adequate resources (financial and other) and the need for suitable planning and coordinating by knowledgeable leaders. The emphasis is mainly on engaging and developing involvement and collaboration from the public community, agreeably the most effective path we can choose.

Strategic Questions

• What are some of the challenges of trying to apply a conservation paradigm to dynamic ecosystems? Is this the right thing to do?

This is a particularly fascinating question. Conserving a single version of an always-changing system seems fundamentally incorrect. Arguments on both sides of this issue can very compelling, with the most certain resolution that we still have so much to learn. I will admit that my personal inclination usually tends towards fewer interventions, even though the devastating effects of invasive plant species here (and many other places) cannot be simply ignored.

• What role can governments and their policies play in supporting urban biodiversity in this community and other communities?

This seems to be a critical part for effective ecological restoration and conservation. Either from the advice and guidance of experts, or in response to community-based initiatives, governments need to strengthen and expand policies that protect natural places—through regulation and education. As this case study suggests, these should aim to limit the introduction of invasive species and other damaging activities, while supporting community enterprises in line with these goals. Governments should also seek ways to provide greater funding/credits, and professional guidance to appropriate community projects.

• Is social capital necessary for dealing with urban biodiversity?

Social capital is definitely necessary for dealing with urban biodiversity. The problem is large, and already involves people in so many ways that solutions need to take advantage of human capital. People need to become engaged stakeholders so that they can become agents of change, and active in the work. As the study correctly states, governments do not have the “capacity, knowledge, or political will to act on this problem in isolation.”

the interconnectedness of it all

The Urban Biodiversity case study raises some very interesting points about cross-sector collaboration. While the two case studies differed in the levels of government and community involvement, studied together Nathalie Dechaine and Chris Strashok were able to highlight some of the key strengths and weaknesses both sectors provide to these kinds of initiatives. Key strengths for government involvement include; funding, organization, accountability and training – while the community supplies manpower, enthusiasm and outreach opportunities and potential.

The CRD outlines four key means of addressing urban biodiversity: collaboration, education, increased access to resources, and changes to policy and legislation. What I found interesting is how none of these means can work independently. Take increased access to resources – increasing financial, ecological and human capital all stem from increased collaboration between interested parties, not to mention educating the general populous to the benefits and feasibility of these restoration projects. Interestingly enough I noticed that knowledge and information sharing were only brought up as results of collaborative or integrative approaches and not as results of increased access to resources. While knowledge and information could technically fall under human capital I feel that it is important to make the distinction between human capital and intellectual capital. Thanks to major advancements in technology ideas and innovations are so much more readily accessible today than they were five, ten years ago. Communities, not-for-profits, academia and all level of governments are able to access ideas, find out what works and what doesn’t work in other communities, and find ways to improve on past projects and concepts.

This leads directly into Strategic Question # 5 Is social capital really necessary for dealing with urban biodiversity?

Urban biodiversity is not a linear problem. It is complex and requires a systems approach that recognizes the interconnectedness of the different actors and components of sustainability. As previously stated, thanks to advancing technology, such as social media sites, different ideas, movements and programs can reach local and global audiences as they never could before. However, the tangible in-person connections still need to be fostered so that the collaborations can work. And it’s not just getting the different sectors to recognize and work together but also getting them to understand the complexity of the issues and challenges surrounding urban biodiversity. As stated in the case study presented by Dechaine and Strashok, these are not short term fixes, the long term effects of altering, even if it is simply removing invasive species, are unknown and all procedures should be undertaken with caution. Not only the impacts to the environment to the community but also the economic and social impacts must be recognized and assessed when dealing with urban biodiversity.

Longterm vision and public engagement

The issue of invasive species in the CRD is a complex one requiring a clear scientific based vision and long term management planning for mitigating the spread and damage caused by target species. Like many problems capital, both social and financial, are required and inherently lacking. When faced with multiple important social and environmental issues in our community many would question why waste time and resources on a few plants when there are far bigger issues that require attention and resources in our community.

Despite a growing awareness of the importance of mitigating invasive species damage to our local natural areas, there is not a clear understanding of how best to slow or reverse the trend. Multiple agencies tackle this issue with their best approximation of what is required, but do so in virtual islands, surrounded by the enemy just outside the arbitrary boarder of a park. I am not suggesting these efforts are futile, but a holistic region wide campaign must be undertaken to deal with the issue. Tackling invasive species as islands within a sea of inaction will not provide the long-term restoration these efforts desire. Education and engagement of the population must be a key component of any efforts so people know why this is an important tissue, and how they can effect change through their own efforts.

It is challenging, as the ecology of the situation is not black and white. These species have evolved over multiple decades to integrate into the natural ecosystems, good or bad as they may be. Many species have come to rely on the invasives for a portion of their habitat, and removal of these structures and food sources must be done with consideration to the impact this has.

To be effective it seems clear enough (despite the monumental task) that this must be an all or nothing assault on species like scotch broom English ivy and holy. Beatifying a local park as a symbol of our commitment to returning an area to the natural state is a political gesture more than an actual ecological solution. There must be buy in by a larger segment of our population, with driven efforts to tackle this problem on all fronts. There has to be a ban on the sale and use of the worst offenders, and an education campaign of the population to why this is. In fact, without government mandates or legislation to enact these rules, pressure from an informed populous to get local nurseries to stop carrying these species could be a major achievement. Community based social marketing campaigns could not only educate residents, but also gain commitment and follow through for the cause, and in turn pressure others to follow. New norms need to be established to help unify the cause, and is as important as pulling invasives out of the ground.

With limited resources being the primary hurtle to effecting true and lasting change in the battle of invasives the effort should be on developing an action plan not specific to geographic boundaries like park boundaries, but to the species of concern. When we have the best scientifically based mitigation plan developed we can mobilize the social capital to tackle this problem in all areas, on both public and private lands. This must be done with considerations to the local wildlife and their evolved reliance of these species. Long-term vision and timelines will be required for tackling this issue, and in developing management plans need to be identified with sound science and strategic vision to guide the process. The must be a long term plan to not only remove and restore, but follow up over years and decades to come. This is where government must take a leadership role.

Considerations of climate change and its inherent impacts to the ecology over time need to be carefully considered. Increases in human use and indirect pressures on these natural areas are forecasted to see, and the education and support of local government and citizens must all also be incorporated into the action plan. Some areas may need to be hit hard and fast, other areas currently unaffected may need to be closed to the public to protect against contamination. Biosecurity measures like boot washes and clothing inspections may need to be started. Perhaps these systems will do little to prevent the spread of invasives, but the awareness and educational opportunities of such programs may go a long way for the greater good.

When reviewing other invasive species programs in other areas of the world, anything short of a direct and total attack on the species of concern seems to be futile. For example rat eradication efforts in areas like South Georgia Island in the Southern Ocean highlight an approach of sound science based management planning, with collateral damage and acceptable risks of damage to native species when considering the long-term benefits for the entire ecosystem (http://www.sgisland.gs/index.php/(e)Eradication_Of_Rodents).